SUMMARY OF KEY FINDINGS:

In our findings, we identified three different segments among individual donors: members of religious groups, effective altruists, and directors of charitable organizations. Despite their different backgrounds and experiences with altruism, all three groups face similar challenges in charitable giving. For one, all of them in some way suffer from a lack of information and knowledge. For religious members, their altruism is guided and heavily influenced by the church, limiting their knowledge around how they can have greater impact. For effective altruists, assessing the impact of charities and finding accurate information makes the charity selection process uncertain. For executive directors, their knowledge of effective charities is limited to whatever they can find via their own networks and local communities. In addition, all three groups greatly benefit from community and human interaction in the giving process. Intimate relationships and experiences with the church community inspires members of religious groups to give. Effective altruists talk with other altruists in making decisions, as well as seek to increase conversation and engagement around effective altruism. Finally, executive directors make their connections with charity’s available for others people to benefit from. Finally, we noticed a common recurring issue of the need for convenience in the charitable giving process i.e. finding charities, choosing ways to give, etc. To address the issue of “convenience” in giving effectively, there are two different approaches we can take. The first is that we can lower existing barriers to giving, such as decreasing the time and effort needed for people to give. The second option is to find ways to make the extra effort necessary to give effectively more immediately gratifying along every step of the way. We would like to explore this second option by finding the appropriate reward mechanisms and reinforcements to make conducting due diligence on charities enjoyable.

CONTEXTUAL INQUIRY RESULTS FROM PARTICIPANTS:

Local Churchgoer: We attended Sunday Mass at St. Patrick and St. Raphael’s Catholic Church. When donation baskets were handed out where people could put in donations, we saw a woman sitting nearby put in a couple dollars. After the service, we interviewed her before she left. The woman seemed to be in her later forties and was most likely a resident of the local Berkshire community. She mentioned that for a long while she had not been an active part of the church, but had finally found her way back. Her comment suggests that she has had a longstanding relationship with her religion that has evolved over time. From the data collected, high-priority needs for the local churchgoer include convenience (donating at the service was easy), giving to causes that she cares about (her church community), and seeing tangible impact/evidence of her giving (knowing that her donation is helping others connect with the church makes her feel good). see more.

CLIA Representative: We conducted a contextual inquiry with a representative from the Center of Learning in Action at Williams College. Having been an active part of the organization for several years, her prime responsibilities include matching students and faculty to charitable causes or means of engaging with the community, acting as a liaison between charitable organizations and students by organizing logistics and managing funding, and deciding what charities to reach out to when donations are available. This process involved observing her perform a variety of tasks in her office on campus and asking her questions about the steps she took during her tasks. The whole conversation was audio recorded. Observing a rep from an organization that does charitable work gave us a new perspective on the needs of users from similar groups. High-priority needs for this user include having a simpler, more efficient method of learning and reaching out to charities (she dreaded sending emails and did not appear to have a set method of actively finding charities), discovering non-monetary ways to give (she sought creative opportunities for students to get involved with charities), and having in-person interaction with representatives from charities (she preferred to have important discussions in person). see more.

EA student group members: We attended the Effective Altruism general and board meetings on Sunday, 25 February. Both meetings were held in Paresky 112, one of the Paresky conference rooms, with the board meeting held directly following the general meeting held at 6-7 pm. Both meetings were in roughly round-table format. The general meeting was open and announced to subscribers of the Effective Altruism mailing list, while attendance at the board meeting was restricted to officers of the EA student group. During the general meeting, we took notes without substantially interfering or participating in the meeting. We were able to attend the subsequent board meeting at 7 pm, whereupon we raised questions brought up by our observations in the general meeting. High priority needs for these users, according to the opinions expressed in the meeting discussion, include having widespread impact, seeing evidence of impact to give, being more mindful about how they give, and exploring different giving options. see more.

DESIGN RESEARCH THEMES AND PROCESSES:

High-level Themes:

- Organizations need help to give effectively and assess impact

- There are ways to give other than money, which are not necessarily widely recognized

- There is no single standardized, uniform way that people learn about charities

- People ideally want to have widespread impact, but tend to find themselves committed to “one” charity or cause

- People are more likely to give to causes and organizations that are convenient or close to them

- People want a familiar human connection and in-person interaction

- People need to see evidence of impact and tangible results to give

- Ideally, people should think more about how they give when they give rather than acting on impulse

- People need to be more open-minded in giving and explore giving options

Do these themes, problems, and practices suggest tasks important to design for?

From these themes, the user tasks that are the most crucial to design for are: - Being able to find out about charities relevant to user interests and preferences easily - Exploring a wider range of charities outside one’s location or areas of interest - Locating nearby charities and causes to get involved in - Getting in contact with representatives with charities easily, and through more interactive means such as in-person meetings, phone calls, and video calls - Finding readily available details about charities without having to navigate through ambiguous information - Getting involved with charitable causes in creative and unique ways beyond monetary donations - Connecting and bringing people together through giving - Receiving incentives or rewards for giving to be more motivated to give effectively in the future

Process for identifying these themes:

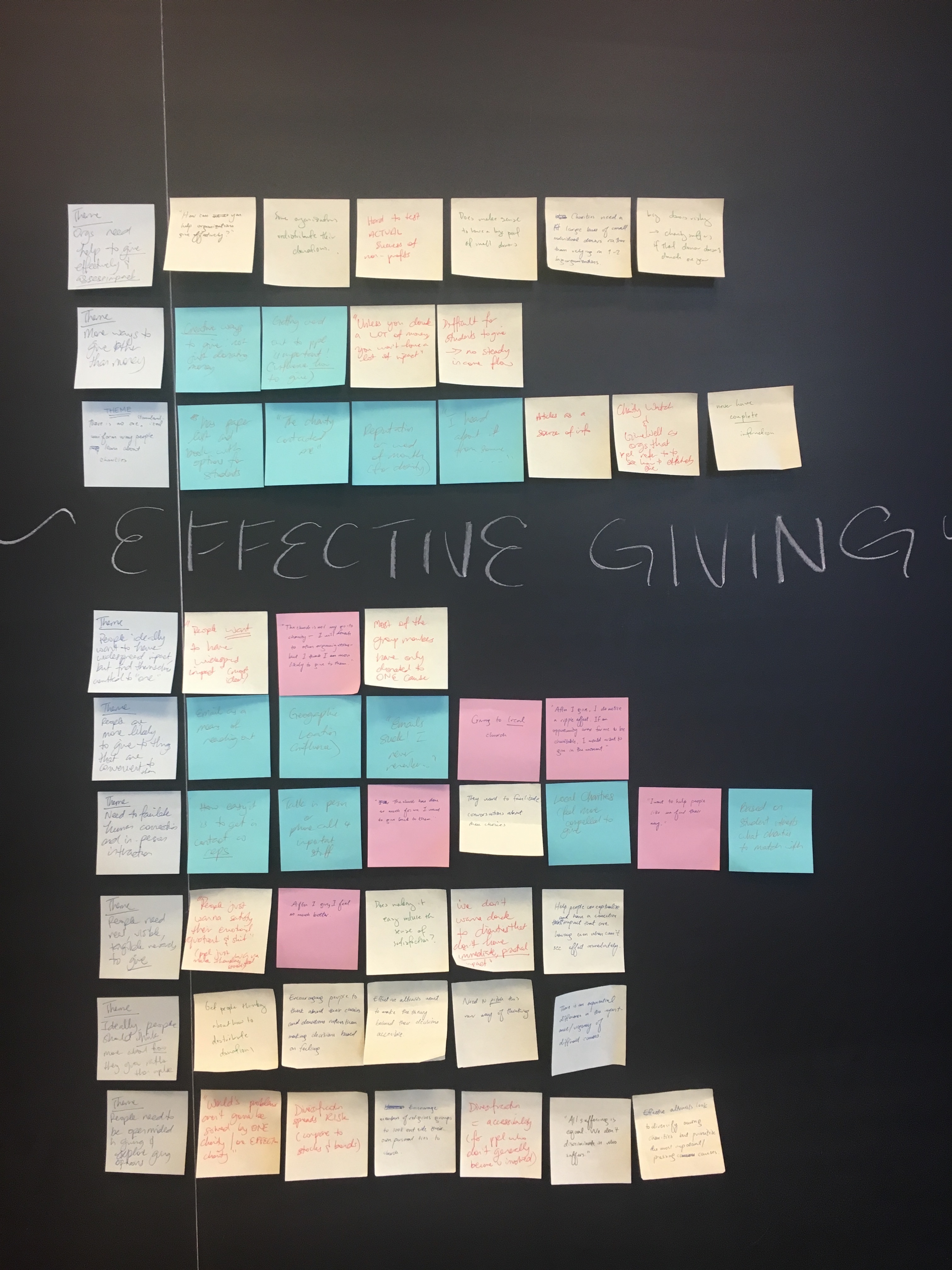

From the data collected from the contextual inquiries we conducted, we made an affinity diagram as shown above. We used different color post-it notes to signify the different user groups that we interviewed/observed (blue for CLIA representative, pink for church goer, and light yellow for student effective altruists). Different pieces of user concerns and information that had a common message were then grouped together and lined up in rows. We created themes that encapsulated each row’s main point and wrote these themes on white post-it notes for each row of user data and used them to label their respective rows.

TASK ANALYSIS QUESTIONS:

Who is going to use the design? The design is to be used by people who may potentially give money or perform services for charities. We specifically investigated three groups: effective altruists, members of local religious groups, charitable organizations themselves, and executive directors of socially oriented organizations. However, any individual can ultimately donate using the Effective Giving app.

What tasks do they now perform? The tasks they perform vary according to demographic group. Members of religious groups donate or provide charitable services most often or only within their church community. Effective altruists focus on donating to effective charities and promoting discussions around thoughtful donation decisions. Consequently, they spend much of their time conducting research, discussing their findings, and weighing their options before making an actual donation. Finally, representatives of charitable organizations spend time conducting research as well as reaching out and connecting to effective charities. Our team has not determined the universality of these different tasks. The variation across user groups indicates that more research is necessary in order to achieve a more holistic, accurate picture of our prospective users.

What tasks are desired? The goal of Effective Giving is to promote thoughtful donation decisions. To that end, we aim to not only increase access to effective charities, but also encourage research, collaboration, and discussion in the donation process. Moreover, we hope to democratize the charitable giving process, by providing non-monetary outlets for our users to have positive impact.

How are the tasks learned? There is no single uniform source by which people learn about charities. Often awareness is spread by word of mouth or reading published articles; for those potential donors who already have a desire to give but don’t know what charities to support, there are lists and organizations (e.g. GiveWell) which publish recommendations. In some cases, charities themselves will reach out. How people learn to make decisions about who to give to and how to connect with charities depends largely on learning from experiences of peers or expert organizations (eg. CLIA) that help guide giving. People learn the process of how to give mainly by information supplied by charities regarding what they need.

Where are the tasks performed? Charitable giving and discovery occur within local churches, the local community, nearby charitable organizations e.g. CLiA, online, and among on campus clubs.

What is the relationship between the person and data? For members of religious groups and charitable organizations, the relationship is personal in many respects. Individual donors give to local charities and to organizations in their immediate community that they know and trust. In addition, they are more likely to give to causes and organizations that are nearby and easily accessible. Executive directors of socially oriented organizations learn from people in their immediate circle about charities of good reputation. On the other hand, effective altruists take a more objective stance toward the data by researching many charities they can donate to, and choosing the ones they believe will maximize the impact of their donation.

What other tools does the person have? Other tools used to learn about, find, and give to charities include emails, phone calls, organizational meetings, word of mouth, and online research. These are all ways people discover charities, but they are not frequently used among individual donors such as members of religious groups.

How do people communicate with each other? Effective altruists communicate with each other with in person meetings and by learning from researchers other effective altruists have already done in order to build off current research and work. Their goal is to have a systematic, thorough process in regard to giving. Working together with other effective altruists is crucial to this task.

Executive directors of social organizations like CLiA communicate in a large variety of ways including, emails, phone calls, in-person meetings. Executive directors need to build up, regularly exercise their networks and send out many leads in order to discover and maintain relationships with effective charities.

Members of individual religious groups connect primarily with their pastors and local church community in order to give charitably. Communication with individuals outside these organizations is not clear.

How often are the tasks performed? Most often, our users perform these tasks according to a set weekly routine. Members of religious groups donate every Sunday at church. Effective altruists discuss their research during weekly meetings. While we know representatives of charitable organizations spend a significant amount of time researching and reaching out to effective charities every week, the exact amount of time spent is not known. Additionally, for all three of these user groups, the time spent on charitable tasks outside of these set schedules is unknown.

What are the time constraints on the tasks? Usually, there are deadlines that charities have to follow (need to get certain projects completed on time, some causes are more urgent like hurricane relief, etc.) so therefore, users need to get these tasks done quickly and efficiently in order to have an effective impact. If it takes too long for people to find out and reach out to charities, and figuring out how to give, people might lose interest in the tasks.

What happens when things go wrong? From the CLIA representative, if the logistical aspect of charity work is too difficult the organization usually chooses another charity to give to. This may be the case for an charitable organization like CLIA, but for the average person, if difficulties arise in giving, they may feel less inclined to give in the future.

For the local churchgoers and effective altruists, it is unknown what their process is for responding to situations where their donations have no impact or negative impact.